language school

Vanja Smoje Glavaski

Introduction

At the mention of a ‘mentor’ in a language school many will find themselves puzzled with the idea. What springs to mind first is probably the notion of a tutor at a teacher-training programme, or a euphemism for a supervisor at a place of work.

However, it is a different kind of mentor that is the focus of my attention in this article. It is a position held primarily by an experienced teacher who is no superior to other teachers in a language school. His or her job, in addition to teaching, is to facilitate the life of new or inexperienced teachers in their workplace and to provide them with subtle, though helpful guidance in their teaching practice – a sort of a systematic professional development during their first term or year at a school. Ideally, a mentor is a kind and open-minded person and a good professional, who will unobtrusively collaborate with a colleague, striving to make him or her rethink everything that happens in the classroom, draw conclusions from it, and endeavour to better him- or herself as a professional through experimentation and constant self-observation.

The idea for a programme of this kind was born to cater for several

needs. First and foremost, it has been recognised that novice teachers

who come straight from teacher training courses, as well as practicing

teachers who have been recently employed by a language school, are in need

of some help and guidance as they are adjusting to the way their new surroundings

function. Also, the academic management needs to monitor such new members

of staff somewhat more closely in order to make sure that they fulfil the

requirements. Last but not least, it is an effort “…to provide some form

of continuous workplace learning to cope with continuous change.”(Caldwell

& Carter, 1997, p. 2) Carruthers (1997) argues that it seems to be

an all-round positive experience: for mentees in terms of acquired knowledge,

skills and support, for organisations in terms of improved performance

and better recruitment, and finally for mentors in terms of their recovered

self-esteem and personal growth (Caldwell & Carter, 1997).

The author of this text was a teacher and the only mentor at an English language school Bell Iskolák, Budapest, with approximately 45 teaching members of staff - and would by means of this article like to share the experience with other professionals in the field who might find the topic worthwile considering and potentially implementing in their schools. It can be said that the scheme gave very good, tangible results at Bell, to the satisfaction of both the academic management and the teachers involved.

Still, the main trait of such a scheme is flexibility and collaboration, rather than the application of prescribed rules. That is why the article contains an example of how the scheme can be conducted, and it is by no means to be considered as an attempt to set fixed standards.

What the mentor does

Here is how a mentoring scheme works in practice. Every term most language schools employ several new teachers who could make up the body of participants in the mentoring scheme. At Bell we thought it useful to hold an induction meeting by the Assistant Academic Manager and the mentor, where new and less experienced teachers are informed about the practicalities of life at the school and are introduced into the ensuing mentoring scheme.

It is the mentor's job to observe each participant at least twice (but the more, the better) during his or her first term, conduct a post-lesson discussion with him or her, provide a clear cut action plan and write a report. The mentor should also be there for the mentees (this is a term I will mainly use to refer to the teachers participating in a mentoring scheme, for the lack of a more fortunate one) for consultations, lesson-planning, or any other kind of help should they require it.

At the end of the term, the mentor conducts a closing meeting where experiences and feelings are summed up, copies of reports are given to individuals and further guidance towards self-development is provided.

What the teachers do

In addition to this, mentees are also expected to conduct several peer observations and discuss them with their partners, as well as to observe some experienced teachers (including the mentor). The number of these observations will vary from case to case, yet again, the more the better. Along these lines, Wajnryb (1992) argues: "Being in the classroom as an observer opens up a range of experiences and processes which can become a part of the raw material of a teacher's professional growth" (p. 1).

Office work

The mentor's job entails some office work such as keeping written records of all the data collected during observations, written reports, observation timetables and feedback sheets. I personally tend to write the reports after the post-lesson discussion as simple records of what has been said. I give a copy of each to teachers only at the end of the term, the reason being that the `official', written feedback might otherwise impair the delicate relationship between the mentor and the mentee (see Appendix 1). However, set office hours are not required; it is probably enough if consultations and post-lesson discussions are scheduled on an individual basis.

Some important concepts in mentoring

It is rather important to mention several crucial concepts on which the whole mentoring scheme is based.

Helping

First of all, help is an essential notion to mention, as being a mentor basically means being a support teacher. However, Gibb (1964) claims that "help is not always helpful - but it can be" if it " is given in a relationship of trust, joint inquiry, openness, and interdependence" (pp. 25-27). Otherwise it may result in resentment, over-dependency, or even offence on the part of the mentee. Nevertheless, a positive, open relationship full of good vibrations can do wonders for both the teacher and the mentor.

Mirroring

As individuals, we all bring with us different background knowledge and experiences, ideas and preconceptions. In addition to that, we see things with different eyes and from different angles. That is why we ought to seek objectivity in recording and giving data as far as we can, or in other words "hold up the mirror", so that the mentee can "see again, or see differently, the events of the lesson and reconstruct their own understandings, so moving along the interteaching continuum" (Malderez & Bodóczky, 1999, p. 19).

Modelling

Being a good model is another key notion. Practice has so far shown that it is better for mentees to observe the mentor first (if possible), and then for the mentor to observe them. This process has positive implications on the mentor-mentee relationship, but it should not imply that the mentor's is the only acceptable teaching style. Malderez and Bodóczky (1999) argue that modelling is shown through almost any professional activity a mentor does in a school - from consulting the literature and attending workshops to interacting with colleagues and students.

Defossilizing patterned behaviour

Teachers start to acquire the real teaching skills when they begin to reflect on what happened in the classroom and analyse it (Tomlinson, 1994). Maingay (1988) argues that many teachers set into pattern behaviour either because they have been teaching like that for many years and have forgotten the principles behind the rituals, or because they are fresh from teacher-training courses and need some constants to lean on in order to experiment gradually. In either case, it is our job as mentors to motivate teachers to think more deeply about what they do and why they do it.

Learning cycle

Moreover, we should encourage mentees to draw conclusions on the basis of their reflection, and experiment further. This idea is based on the learning cycle expressed by Kolb and Schön, which leads to permanent development (Malderez, & Bodóczky, 1998).

Counselling

Some counselling skills will also be needed, when conducting a post-lesson discussion, for example. Therefore, we should be sensitive to mentees' feelings and avoid putting them on the defensive by being over-supportive or by judging and evaluating their actions. It is crucial here that we listen to what a mentee has to say very carefully and by skilful questioning guide him or her towards realisation and learning. In this respect Tomlinson (1994) points out that novice teachers "bring consciously espoused ideals and informal theories about teaching. These need to be allowed expression and examination so that they can be built upon and developed/amended as appropriate" (p. 30).

Models of supervision

Finally, I would like to stress the importance of viewing every teacher as an individual and adapting to their teaching and personal style. Along those lines, Woodward (1998) says "I had only one feedback option in my repertoire. And one wasn't enough for the fifteen very different trainee teachers I was working with I realized that feedback sessions don't have to be a ritual" (p. 127). Gebhard (1990) has recognised five different models of supervision (and mentoring) - directive, alternative, collaborative, non-directive and creative - and encourages experimenting with them with different teachers in different circumstances.

Practical advice for lesson observations

Mentoring mostly focuses on lesson observations. At Bell all observations are set up in advance and there are no "surprise visits", but this practice could be different in other schools. Prior to the first observation of a new teacher, the mentor usually invites him or her to see a lesson of theirs and have a chat about it. That way teachers can be reassured that mentors are trying to build an open relationship based on trust with them and that the same set of rules applies both to them and their mentor.

Pre-lesson discussion

Since it is advisable that observations are arranged in advance (their aim not being supervision and evaluation), it seems logical that the mentor and mentee should have a short, 10-minute chat prior to them. First of all, this gives the teacher a chance to explain what will be going on in the classroom and to inform the mentor about the class in general. Thus, the mentor gets a clearer picture of a new set of circumstances, which must be taken into consideration when analysing the observation data later on. For example, a teacher told me once that his class of three 11-year-olds did not work well together, due to differences in level and personality. He catered for their individual needs by devising a set of project-based lessons where each student worked on his or her own. It was crucial for me to know the background of this decision because otherwise I might have formed unjustified conclusions.

Furthermore, in the pre-lesson discussion a teacher can acquaint the mentor with the lesson plan and choose the focus of the observation. The latter seems extremely important to me, because that way the teacher decides what aspect of their teaching they would like to examine and develop, and the mentor primarily aids this process as a data-collector and a consultant. The aim here is for the teacher to acquire control of his or her own professional growth. Woodward (1998) writes in favour of this idea: "Observing need not be done in order to assess someone. Instead, observers can watch for what teachers or students have asked them to watch for" (p. 135).

During observation

Being observed is not very enjoyable, as many teachers will confirm. The observer is often perceived as an intruder who breaks the delicate balance of an otherwise harmonious class and who gets only a snapshot of what teaching that class really is. That is why a sequence of observations might give us a more objective picture.

Literature tells us that in order to make an observation as objective as possible, it is advisable to use an observation tool, such as a chart, diagram or notes, "a focused activity to work on while observing a lesson in progress" (Wajnryb 1992, p. 7). A number of observation tasks can nowadays be found in published sources. Teachers could also be acquainted with these at the introductory meeting or at a pre-observation discussion, as they might want to use them to observe their peers, experienced teachers, the mentor, or themselves with somewhat greater focus.

In general, follow the common-sense rules of conduct when observing. Announce your visit, arrive on time and leave when the lesson is finished, do not interrupt or participate in the activities unless you are asked to, smile a lot and tell the teacher something nice before you leave (RSA CELTA Course at International House, Budapest, June 1999, personal communication).

Although as mentors we try to be virtually non-judgmental, it is possible to use a list of assessment criteria during observation. Such a tool is most frequently employed as a checklist and can be utilised at a post-lesson discussion by asking teachers to evaluate their own teaching on the basis of the compiled criteria. That will often result in the teachers' self-realization of their weaker points without the mentor pointing them out. Naturally, the teacher should be acquainted with the criteria in advance.

Post-lesson discussion

There are two basic ways of scheduling a post-lesson discussion (PLD) - immediately after the observed lesson, or several days later. I, personally, have chosen the latter for several reasons. Namely, most teachers have tight timetables and lessons usually follow the observed one. Also, the time period between the observed lesson and a PLD allows both the mentor and the mentee to reflect more closely and objectively on their teaching. The drawback of this is that some details of the lesson are inevitably forgotten by the time of the PLD.

It is essential that the mentee feels relaxed during the PLD, and that is why the mentor should choose to conduct it in a room where he or she and the mentee are not disturbed, and should choose to sit close to the mentee. He or she ought to constantly be aware of his or her body language and use it consciously to put the teacher at ease.

There are several phases of a PLD: climate setting, reflecting, learning and planning. During the first phase the mentor tries to achieve a relaxed atmosphere for the ensuing dialogue. During the reflection phase, the mentee talks about his or her lesson, analysing it in accordance with the previously chosen focus of observation, whereas the mentor listens actively, using "I-statements" to show his or her angle of seeing things. (Malderez & Bodóczky, 1999). Woodward (1998) notes: "This combination of talking and non-judgmental listening allows for a release of nervous energy by the teacher and lifts the burden of comment from the listener" (p. 130). In the learning phase the mentor challenges the teacher by asking further questions. Finally, they come to a conclusion and agree on an action plan to cater for the teacher's needs. In this last phase the mentor can recommend relevant literature, refresher courses, further training, in-service workshops, self-observation, peer-observation, observing the mentor or another experienced teacher, implementation of an alternative teaching method, etc. Naturally, these phases intertwine as PLD progresses, and it is a trait of a skilful mentor to achieve them all and still retain unbroken the flow of dialogue, positive feelings and thought. If a teacher emerges from a PLD with positive emotions of support and understanding, and yet with a clear realistic task for further development ahead of him or her, something has been accomplished.

Still, literature warns us that "these interventions will either enhance, impede or send off-course the mentee's development. It is, therefore, essential that the mentor is as conscious as possible of the potential impact of everything he or she chooses to say and do" (Malderez & Bodóczky, 1999, p. 85)

Consultations and further support

Consultations

Occasionally novice teachers will turn to their mentor to ask for a piece of advice or help in a certain matter. Those can range from looking for a suitable activity for one lesson, telling you about a discipline problem and complaining about different-ability classes, to asking for your advice and support on experimenting with an alternative approach.

In my experience, no specific times for consultations need to be appointed, but the mentor should try to be in the library or staff room with teachers as much as possible. If someone comes forward with a problem or doubt, a meeting can be scheduled to work on it. That seems to have worked at Bell, so far as the teachers knew that the mentor was there for them. Moreover, the mentor's time is not wasted on waiting for teachers in appointed hours.

The guiding principle in solving problematic issues ought to be to involve the teacher in finding the solution as much as possible, i.e. to collaborate on it, and not just to impose one's own ideas on them. This way the teacher is gradually guided towards a possible solution, but also towards his or her own path of growth and self-development in the future.

Lesson planning

Among other things, short-term and long-term lesson planning might turn out to be a problem for a new teacher. Once again, the mentor should try to work with the teacher on this issue, and the teachers certainly appreciate such an attitude. I have also found that it helps if mentees look at the mentor's lesson plan when they observe his or her lesson and afterwards hear his or her reasons behind certain stages.

Lesson planning can also be utilised as a part of the action planning process during a PLD. A mentor may ask mentees to rewrite their lesson plan, or to write a new one for the same or the following lesson.

Co-planning with mentees for their lessons is another idea and sometimes it gives better results than reflecting on their teaching in PLD, because they tend to grasp the principles behind staging and making choices in the classroom. Woodward (1998) recognises the need for this when she states: "Trainees can become over-concerned with getting a set sequence of procedures technically correct regardless of what is actually happening in the classroom" (p. 128).

Mentor's own further development

There would not be much sense in talking about teachers' further development if it did not imply and promote that of the mentors.

Recommended literature

It is natural for any professional to start bridging the gap in their knowledge by reading relevant literature. There is nowadays a number of publications written about mentoring both by Hungarian and international authors.

Mentoring courses

Just like teachers, good mentors are not born as such. First of all, they ought to be solid teachers who can provide a good model for their mentees in terms of teaching methods, knowledge of resources, enthusiasm, etc. Moreover, Walker and Stott (1997), as well as many other professionals in the field argue that mentors need formal training and preparation, as well as theoretical knowledge (Caldwell & Carter, 1997). To cater for this need, Caroline Bodóczky and Angi Maldarez set up a term-long mentoring course at Eötvös University, Budapest a number of years ago. I have, to my great satisfaction and benefit, attended one such course specifically organised for mentors at language schools, and I sincerely recommend it to all future and practicing mentors.

Self-observation and peer observation

In order to enable our professional growth as mentors, we can employ some ideas that we advise to the participants of the mentoring scheme. Thus, we can use self-observation tasks in order to observe and reflect on our own behaviour during PLD. Alternatively, we can ask a colleague mentor or another teacher to observe us as we conduct a PLD and later analyse the data with us. (For the second option, we will need to have observed the same lesson together previously.)

Feedback from the teachers

No mentoring scheme would be valid, I believe, without the mentor gathering the responses of those for whom the scheme was designed in the first place - the teachers. Consequently, I decided to ask for the teachers' official feedback on two occasions during the term (but mentors could opt to do it more often unofficially). The first might occur around mid-term and is conducted so that the mentor can get the idea of how much has been accomplished so far and how the mentees feel about it. It could also serve as a kind of reminder for teachers to start their peer observations and observations of experienced teachers if they still have not. The second one should happen at the end of the term and might be incorporated in the closing meeting. Its purpose is for the teachers to sum up what they have learnt and felt and give any suggestions for the future schemes.

The comments are anonymous and extremely valuable as they help the mentor to form a picture of what the experience has been for his or her colleagues, and guides him or her towards adjusting it subsequently. Here is how some of my mentees put it: "I think the whole thing has been really useful. I got a lot of new ideas I can use in class or just keep in mind." "I found the whole scheme very valuable: getting feedback, encouragement and suggestions has helped me a lot." "It's been constructive; given some focus to our personal assessment of [our own] lessons" (anonymous, December 13, 2000; personal communication) (see Appendix 2 and 3).

Reviewing and modifying the scheme

To go back to the `continuous workplace learning' mentioned at the beginning of the article, I must emphasise again that the scheme I have described here is only an example of how it could be done and that no school would be learning and growing if it did not reflect and modify its activities from time to time. That is why I strongly suggest that annual meetings with the Academic Management are held and the success of the previous practice evaluated.

In conclusion, I hope that the reader of these lines will find the idea

of mentoring in a language school environment at least intriguing and hopefully

useful. Those mentors who do decide to try it out, though, should feel

free to adjust the scheme according to the circumstances in their own school,

new developments in methodology, the requirements of the Academic Management,

the needs of their mentees and their mentoring style.

References

Caldwell, B. J., & Carter, E. M. A. (Eds.). (1997). The return

of the mentor: Strategies for workplace learning. London: The Falmer

Press.

Carruthers, J. (1997). The principles and practice of mentoring. In

B. J. Caldwell, & E. M. A. Carter (Eds.), The return of the mentor:

Strategies for workplace learning (pp. 9-24). London: The Falmer Press.

Gebhard, J. G. (1990). Models of supervision: Choices. In J. Richards

& D. Nunan (Eds.), Second language teacher education (pp. 156-166).

Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Gibb, J. R. (1964). Is help helpful? YMCA Association Forum and

Section Journal, 55, 25-27.

Maingay, P. (1988). Observation for training, development or assessment?

In T. Duff. (Ed.), Explorations in teacher training (pp. 118-131).

Harlow:Longman.

Malderez, A., & Bodóczky, C. (1999). Mentor courses.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tomlinson, P. (1994). Understanding mentoring. Buckingham: Open

University Press.

Wajnryb, R. (1992). Classroom observation tasks. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Walker, A. & Stott, K. (1997). Preparing for leadership in schools:

The mentoring contribution" In B. J Caldwell, & E. M. A. Carter (Eds.),

The

return of the mentor: Strategies for workplace learning (pp. 77-90

). London: The Falmer Press.

Woodward, T. (1998). Ways of training: Recipes for teacher training.

Harlow: Longman.

Appendix 1

Post-observation report

Observer:

Teacher:

Date and time:

Place / Class:

Number of Students, Age, and Gender:

Unexpected circumstances:

Date and time of post-observation session:

POINTS COVERED:

a) Things that we both felt good about:

b) Things we agreed need working on:

ACTION PLAN:

COMMENTS:

Appendix 2

Dear Teacher,

Our pilot mentoring scheme has now been in progress for almost half a term and I am curious to know what we have accomplished so far.

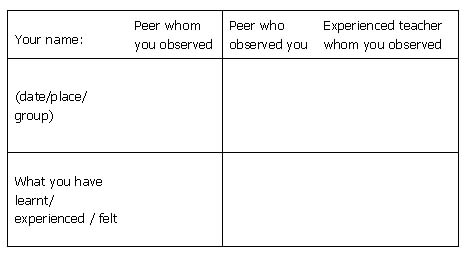

Therefore, I would kindly like to ask you to fill in the chart that follows and put it in my pigeon hole. Please do fill in the second row as well, since I am more than interested in how you have experienced the whole scheme so far.

Attached to this sheet of paper you will find a post-it note. Please use it for any other comments / suggestions / questions etc. that you might have in connection to the whole scheme (mentor's observations, post-observation discussions, organization). This is important feedback for me and your colleagues, and will influence how we shape this scheme in the future. The post-it-note feedback is anonymous. Please, stick the notes into my pigeon hole as well.

Thank you for the time and effort.

Appendix 3

End-of-term feedback sheet

Please comment on the following aspects of the mentoring scheme:

Your expectations from the mentoring scheme and to what extent they were met

Organisation of the scheme (e.g. timing, schedule, meetings)

Peer observations

Mentor's observations

Post-observation discussions

Long-term planning

Mentor's help and support

What you have learnt from the scheme

Any suggestions you might have for the scheme in the future

Thank you! :)

Vanja Smoje Glavaski graduated as an EFL teacher from the University of Belgrade. She taught at the Department of English Language and Literature of the University of Belgrade University and at Bell Iskolák, Budapest, where she also worked as a mentor.