How coursebook dialogues can be implemented

in the classroom

Edwards Melinda and Csizér Kata

As language teachers we have often experienced miscommunications and communication breakdowns among our students. What we have observed is that even advanced learners of English are often not aware what social, cultural and discourse (in one word pragmatic) conventions have to be followed in various situations. At the same time we have had the impression that coursebooks usually do not place enough emphasis on the teaching of pragmatic competence. Therefore, we set out to find out whether this claim can be justified by a thorough analysis.

In this article, we first investigate the presence of openings and closings in two coursebook series: Headway (Soars & Soars, 1989-1998) and Criss Cross (Ellis, Laidlow, Medgyes & Byrne, 1999). We chose openings and closings as we consider their role significant in conversations (see Hartford & Bardovi-Harlig, 1992), and because they often pose problems for Hungarian students due to the differences between the two languages. Consider the different roles the question How are you? or the greeting/leave-taking Hello plays in English versus Hungarian conversations. In the second part of the article, we offer teaching tips for practising teachers in order to improve their students' pragmatic competence by supplementing the existing coursebooks.

Background to the investigation

Since communicative competence and communicative language pedagogy appeared on the stage of language teaching and research, teachers have been aware that there is more to language learning than memorising vocabulary and grammar rules. As communication "takes place in discourse and sociocultural contexts which provide constraints on appropriate language use and also clues as to correct interpretations and always has a purpose (for example, to establish social relations, to persuade, or to promise)" (Canale, 1983, pp. 3-4), communicative competence has been defined accordingly. However, at this point, we are more interested in one distinct part of communicative competence, namely pragmatic competence. For the purposes of this investigation pragmatic competence was defined as the knowledge of social, cultural and discourse conventions that have to be followed in various situations.

In an article entitled `Developing pragmatic awareness: Closing the conversation' (Bardovi-Harlig, Hartford, Mahan-Taylor, Morgan & Reynolds, 1996), the authors highlight the importance of pragmatic competence by arguing that:

They also point out that greetings and closings, not to mention more complicated speech acts, cannot be "transferred from one language to another" (p. 324) because there are differences in the content and the formula as well. Examining closings in English as a Second Language (ESL) coursebooks, Bardovi-Harlig et al. concluded that the "lack of complete conversational models leaves students unaware of both the proper way to end a conversation and the signals speakers may use when they are ready to terminate an exchange" (p. 329).

Speakers who do not use pragmatically appropriate language run the risk of appearing unco-operative at the least, or, more seriously, rude or insulting. This is particularly true of advanced learners whose high linguistic proficiency leads other speakers to expect concomitantly high pragmatic competence (p. 324).

The question we face is whether English as a Foreign Language (EFL) coursebooks also lack conversational models? This question is of high importance, as the role of conversational models is even more important in an EFL than in an ESL context, due to the scarcity of foreign language input in everyday life. Both coursebooks and teachers have more responsibility in providing the necessary input for the students to enhance their communicative competence.

Research has shown that EFL learners and their teachers tend to underestimate the seriousness of pragmatic violations, and consistently rank grammatical errors as more serious than pragmatic errors, whereas ESL learners and teachers showed the opposite attitude (Bardovi-Harlig & Dörnyei, 1998). This finding also shows how important it is to draw EFL learners' attention to the seriousness of pragmatic violations.

Some useful definitions

Our investigation was directed at two features of conversations: openings

and closings. Coulthard (1985) describes openings and closings as speech

acts that typically appear as adjacency pairs (such as "Hello! - Hello!"

or "Bye! - Good-bye!"). He highlights the importance of these adjacency

pairs by referring to Sacks (1967), who claims:

... the absence of a particular item in conversation has initially no importance because there are any number of things that are similarly absent, in the case of an adjacency pair the first part provides specifically for the second and therefore the absence of the second is noticeable and noticed (p. 70).English closings must have a terminal pair/exchange, but it often happens that this terminal pair/exchange is preceded by a pre-closing and shutting down the topic, both of which signal the speaker's intention to end the conversation (Bardovi-Harlig et al, 1996). Pre-closings "function to verify that no additional business remains to be negotiated in the conversation" and "if a speaker does not begin a new topic or reintroduce a previous one, then the conversation will end" (p. 328).

In the classification of openings, the following distinctions were made. Based on Bardovi-Harlig et al (1996), who distinguish between partial and complete closings, a distinction was made between complete and partial openings. The basis of this categorisation was whether they contain a post-opening (our term) or not, e.g. How are you? In other words, post-openings are the utterances that come between the greeting (Hello, Good morning, etc.) and the main body of the conversation.

In sum, a complete opening contains greeting in form of an adjacency pair and includes a post-opening, as in the example:

(1)

A Hello, John.

B Hi, Peter. How are you today?

A Fine, thanks. And you?

B I'm OK, thanks.

In a similar way, a complete closing is made up of a pre-closing/shutting down the topic and a terminal pair (adjacency pair). For example:

(2)

A Sorry, Jim, but I must be going now. Can you give me a call tomorrow

about the meeting?

B Yes, sure, I'll call you from work.

A Thanks very much. Bye now!

B Bye Steve!

Investigating conversations

In our investigation we intended to examine how many conversations the coursebooks contained and how they were presented. We also looked at whether these conversations contained openings and closings. The differences between the two coursebook series, Headway and Criss Cross, concerning conversational models were also analysed.

We hypothesised that lower level coursebooks would pay more attention to pragmatic awareness, while higher level books would emphasise other aspects of teaching, such as vocabulary, and devote less attention to pragmatic awareness. It was also hypothesised that partial openings and closings are in majority and complete openings and closings are underrepresented. We expected to find differences between the two coursebook series based on the differences in the target audiences, and we were interested in how these differences between the two series are manifested in the teaching of pragmatic competence.

At this point it is important to justify our choice of the two coursebook series. The Headway series was chosen because in secondary education this is the most widely used coursebook in Hungary (Nikolov, 1999). The series has five levels from Elementary to Advanced with the aim of helping students to speak both accurately and fluently. It is written for an adult/young adult international audience. The Criss Cross series, from Beginner to Upper-Intermediate, was written for a Central European secondary level student-population. The student books were written by an international team but the practice books are country-specific. Among the aims of the coursebook we can find the intention to provide a culturally stimulating book that recognises "the need for cross cultural awareness and a European dimension to education" (Pre-Intermediate Coursebook, p. 3).

After choosing the coursebooks, we identified the conversations in them. We considered an item conversation if the book itself labelled it conversation. There were only a very small number of cases where a one-sentence line was labelled conversation in the coursebook; those cases were not included in our analysis. On the other hand, there were a handful of cases where a conversation was not labelled as one by the authors, those cases were included in our analysis. After identifying the conversations, we tallied how many of them contained openings and closings, and they were collected on separate sheets in order to help the analysis.

Findings

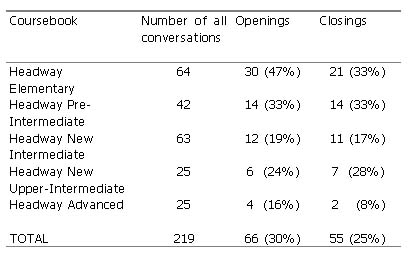

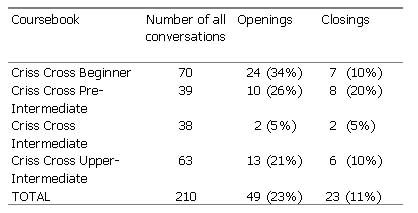

The following two tables show the number of conversations in the coursebooks, as well as the openings and closings found in them. The two series are presented in separate tables.

Table 1. Conversations with opening and closings: Headway

Table 2. Conversations with opening and closings: Criss Cross

Although the Criss Cross series contains almost the same number of conversations in fewer books, the number of openings and closings found in those books is lower than that in the Headway series. This is surprising because Criss Cross was edited by an international board with the aim of taking national characteristics into consideration, therefore we expected that more emphasis would be put on the teaching of greeting and saying good-bye.

In the coursebooks altogether, openings outnumber closings. There are only two books out of the nine, where the number of openings and closings is equal. In our view, this does not suggest that saying `hello' would be more important than saying `good-bye' from a pragmatic point of view. The reason might be that the absence of openings is visually more apparent while conversations can easily be finished by adding three dots.

The number of conversations does not seem to be influenced by the level of the books. Both Headway Intermediate and Criss Cross Upper-Intermediate contain almost as many conversations as the Elementary/Beginner books. On the other hand, our results show that that the higher the level of the coursebook is, the fewer openings and closings there are in the books: two-thirds of all openings and closings can be found in the first two books of the series.

The sheer number of openings and closings does not indicate whether there is systematic teaching of pragmatic comperence. Therefore taking a closer look at openings and closings is in order.

Openings

One of our aims was to examine how adjacency pairs are represented in the coursebook conversations. It was often found that adjacency pairs were incomplete. We have to remark that this phenomenon is very different from real life situations, where not only is the absence of the second half of the adjacency pair noticeable (Coulthard, 1985), but it usually communicates something. It can signify the addressee's unwillingness to respond (due to anger, for example) or the fact that he did not notice his partner. In coursebooks, however, the lack of a full adjacency pair may simply be due to lack of space, where the writers wanted to "get to the point" instead of including full adjacency pairs and post-openings.

The analysis showed that most of the openings in the conversations are partial, that is, there are few conversations that contain post-openings, such as `How are you?' or `Pleased to meet you'. Concerning this observation, there are no significant differences between the two coursebook series. The most complete type of conversations were those conducted on the telephone - a result that may be due to the stricter formula or the lack of non-verbal communication.

The majority of the openings are one-way, meaning that only one of the participants greets the other one and the second half of the adjacency pair is missing. Two examples are quoted to demonstrate this phenomenon.

(3)

A Hi, Mum! Here's the shopping.

B Thanks. Oh, it's heavy" (Criss Cross Beginner Student's Book, p.

28.)

(4)

A Tim, this is Zsuzsa. She is from Hungary.

B Hello Zsuzsa. This is a nice name. How do you say it in English?

C Susan. (Criss Cross Beginner Practice Book, p. 13.)

Closings

While the four books of the Criss Cross series contain only one complete closing, the Headway books give 15 examples of these. However, even in the case of the Headway series, the partial closings are more in number. This lack of complete closings can be explained by the fact that most of the time the aim of the conversations in the coursebooks is to present new grammar, or provide texts for reading or listening comprehension exercises where the endings of the conversations are not important because no questions are attached to them. But this lack of conversation models of closings might result in the fact that students will not be able to leave a conversation without sounding impolite, abrupt, or downright rude.

Pre-closings in the coursebooks often simply mean one of the characters saying thank you. For example:

(5)

A Good morning, sir. Can I see your ticket?

B Yes, of course. Here you are.

A Thank you. Maidstone next stop.

B Thank you. (Headway Elementary Student's Book, p. 23)

(6)

J It's all right. I will pick you up as well. It's no trouble.

B That's great! Thanks a lot, Jenny. (Headway Pre-Intermediate Student's

Book, p. 35)

Terminal exchange is often missing, and if it is present at the end of the conversations, it is often one-way. For example:

(7)

Rosie: Thanks very much. Thanks for your help. I'll go to oh, sorry,

I can't remember which hotel you suggested.

Clerk: The Euro Hotel.

Rosie: The Euro. Thanks a lot. Bye. (Headway Intermediate Student's

Book, p. 139)

It is unlikely in such a situation in real life that the clerk does not say goodbye and does not add, `Have a pleasant stay!; or something similar. For contrast, observe the richness of pre-closings in a conversation presented by Bardovi-Harlig et al. (1996, p. 334).

(8)

A I'd love to continue this conversation, but I really need to go now.

I have to get back to the office.

B Well, let's get together soon.

A How about Friday?

B Friday sounds good. Where shall we meet?

A (looks at watch) You know, I really must be going now or I'll be

very late. Can you give me a call tomorrow and we'll decide?

B Fine. Speak to you then.

A Sorry I have to rush off like this.

B That's OK. I understand.

A Good-bye.

B So long.

The conversations in Examples 6 and 7 can be made more natural and real-life by complementing them with pre-closings and full adjacency pairs.

Teaching implications

As we have seen from the investigation, coursebook conversations need to be supplemented in order to provide the necessary pragmatic input for students. In both of the investigated coursebook series there are sections and activities that aim at teaching and practising speech acts and language functions. In Headway Upper-Intermediate (p. 57) there is a section called Beginning and ending a telephone conversation where students have to put the parts of telephone conversations in the right order. After this, they have to answer the following questions: Who's trying to end the conversation? Who wants to chat? How does Andy try to signal that he wants to end the conversation? How do they confirm their arrangement? As for beginning a telephone conversation, formal and informal conversations are explored and compared in the exercise. These exercises provide good examples for teaching pragmatic skills and raising pragmatic awareness.

As far as resource materials are concerned, without the aim of providing

a comprehensive list, we would like to refer to two resource books as well

as to some of our own ideas. Functions of English (Jones, 1981) offers

a great number of activities for practising conversational rules. Here

we would like to quote some with the focus on openings and closings.

(You are in group A.) In this activity you have to pretend to be very confident. The idea is for you to start a series of conversations with different people in group B. In real life you have to be quite brave to do this - practice in class will help you to become confident. Treat the classroom as a place where you can experiment.End each conversation by saying: `Well, it's been nice talking to you, but I really must be going now. Sorry to rush off.' Then find anther member of group B to start a conversation with! (p.138).

(You are in group B.) In this activity a number of people from group A are going to start conversation with you. There's no need to be unfriendly, of course, but let them do all the work. Let them start each conversation and find a way of finishing it. Let them ask the questions. Stand up for this activity. (p.100).

Activity 136. (You are still in group A.) This time it's your turn to be the passive partner. Stand up and wait for people from group B to start conversation with you. Let them ask the questions and finish each conversation.(p.134).

Activity 16. (You are still in group B.) This time it's your turn to take the initiative and start conversation with people in group A. The idea of this activity is to give you a chance to experiment and build up your confidence _ in real life you need to be quite brave to start conversations.

End each conversation by saying: `Well, I've really enjoyed talking to you, but I must be off now. See you later, perhaps.' Then find another member of group A to start a conversation with. Stand up and find someone to talk to now! (p.94).

There is another excellent resource book, Conversation and dialogues

in action (Dörnyei and Thurrell, 1992), which provides useful

classroom activities. These activities practice a variety of conversational

rules and strategies, such as changing the subject, interrupting or bringing

a conversation to a close. For example the authors present 23 different

pre-closings, such as:

I've got to go now / I've got to be going now.

I'd better let you go / I'd better not take up any more of your time.

I (really) must go / must be going / must be off now.

Well, I think I'll let you go.

So I'll see you soon/ next week.

Take care.

The main aim of the authors is to raise students' awareness of the importance of conversational rules, and to provide input and practice. Most of these activities require little preparation, and almost any coursebook conversation can be used for these purposes.

Dörnyei and Thurrell's (1992) ideas can be further developed. For practising closings, students can act out a situation where they are trapped in a conversation with a neighbour and they are in a hurry to leave. Another option is that they write a mini-sketch entitled Can't say goodbye, when two lovers are unable and unwilling to say goodbye to each other. In both cases the importance of shutting down the topic and pre-closings can be highlighted.

In order to provide more input, conversations without an opening, post-opening, pre-closing or closing can be rewritten and completed. Students can be asked to act them out in different situations (standing in line in a shop vs. meeting a friend for the third time at school). They can also act out or rewrite conversations with the roles containing power-relationships. As an example, the class can discuss how the conversation would be different were it not between colleagues, but a head manager and an employer. Of course the focus of these activities goes beyond openings and closings, and they can practice other speech acts, functions and politeness rules.

Conclusions

We find that the simple presence of input might not suffice to raise students' pragmatic awareness, therefore it is the teachers' responsibility to use the materials in a way that they contribute to the pragmatic development of students. We hope that the suggested resource books and ideas such as role-plays, conversation completion activities and explicit teaching of useful phrases in connection with opening and closing a conversation will enrich the teaching practice of many of our readers. We also hope that our own small-scale investigation might encourage some colleagues to look into other aspects of teaching pragmatic awareness and share their ideas with the rest of us.

References

Bardovi-Harlig, K., & Dörnyei, Z. (1998). Do language learners

recognise pragmatic violations? Pragmatic versus grammatical awareness

in instructed L2 learning. TESOL Quarterly 32, 233-259.

Bardovi-Harlig, K., Hartford, B. A. S., Mahan-Taylor, R., Morgan, M.

J., & Reynolds, D. W. (1996). Developing pragmatic awareness: closing

the conversation. In: T. Hedge, & N. Whitney (Eds.), Power, pedagogy

and practice (pp. 324-337). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Canale, M. (1983). From communicative competence to communicative language

pedagogy. In J. C. Richards & R.W. Schmidt (Eds.), Language and

communication pp. 2-27. Harlow: Longman.

Coulthard, M. (1985). An introduction to discourse analysis. London:

Longman.

Dörnyei, Z., & Thurrell, S. (1992). Conversation and dialogues

in action. London: Prentice Hall International.

Hartford, B. S., & Bardovi-Harlig, K. (1992). Closing the conversation:

Evidence from the academic advising session. Discourse Processes 15,

93-116.

Jones, L. (1981). Functions of English. A course for upper-intermediate

and more advanced students. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nikolov, M. (1999). Classroom observation project. In M. Nikolov, H.

Fekete, É. Major (Eds.), English language education in Hungary.

A baseline study (pp. 221-245). Budapest: The British Council,

Hungary.

Edwards Melinda and Csizér Kata are PhD students at Eötvös Loránd University. Edwards Melinda teaches at Pázmány Péter University, and Csizér Kata taught English courses at Katedra Language School.